Do we have the ipsissima verba of Jesus recorded in the gospels? I very much doubt it, but we do have a method and a theory that can help us assess how the tradition of Jesus’s sayings evolved up to the point they appeared in the synoptic gospels. This looks at a particular passage in Matthew and compares it with parallel texts and hazards some conclusions on what Jesus might have said that is of relevance to today.

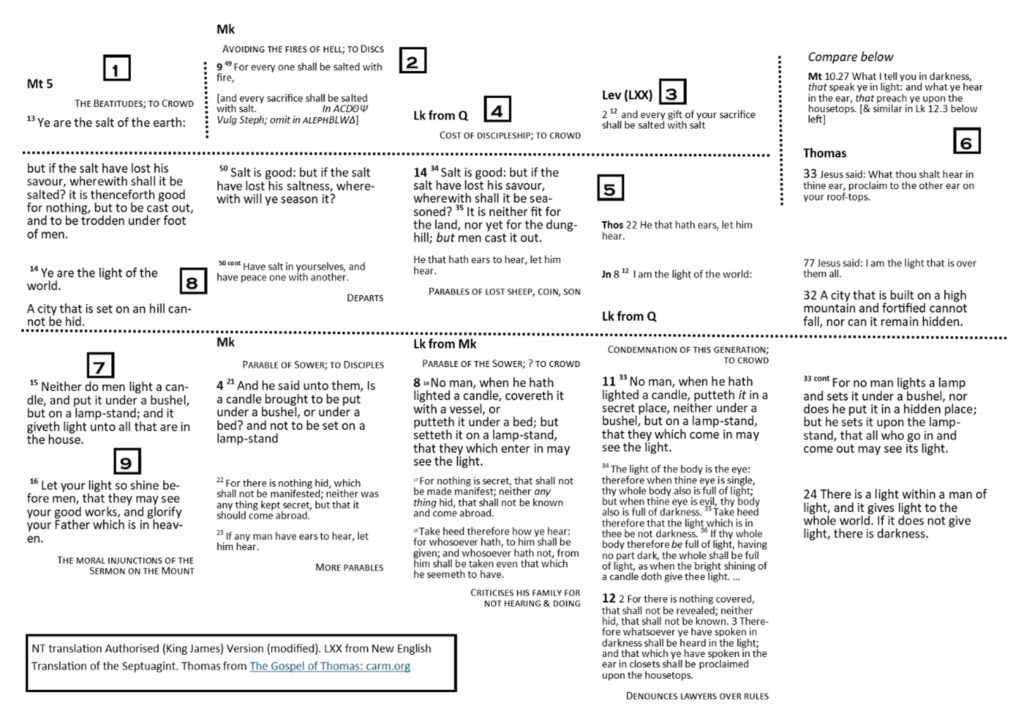

This, I fear, was rather too dense for listeners to follow. I hope it will be easier to read, when one can take time and look back and forth between the text and the diagram at the end.

Sermon at the chapel at Churchill College, 4 May 2025

Lev 2.11-13

Mat 5. 13-16

N.B. this refers to the document ‘Analysis of Mt 5’, an image of which is pasted at the end of this document.

“For everyone shall be salted with fire.”

I am going to explore the Jesus tradition in the first three gospels. I am asking, “How much goes back to the historical Jesus, and how that tradition developed up to the time the gospels were written and afterwards?”

The first three gospels, Matthew, Mark and Luke – and, by the way, I shall use these names for the final writers of each gospel without presuming that these were their names or who they were – the first three gospels have much in common. They are often termed the Synoptic Gospels in recognition of this. Why are they so similar and how have the differences come about?

Detailed analysis last century led to a two-source hypothesis. While some disagree, the vast majority of scholars accept this hypothesis and, certainly, I am convinced. Simplified, when Matthew and Luke sat down to write their gospels they had two earlier documents in front of them, from which they copied. One of these was Mark’s gospel; the other a hypothetical document termed Q. Unlike the other gospels, Q had no narrative, only sayings and parables attributed to Jesus.

The main tool to investigate all this is to put the three gospels in parallel and I have produced a small example in the handout. This is based on just four verses from Matthew, chapter 5, verses 13 to 16. To the right of these verses are parallels from Mark and Luke, together with parallels from an apocryphal gospel, that of Thomas. The Gospel of Thomas exists only as fragments of two papyri in the original Greek and a whole text in Coptic. The origin of Thomas is debated: it may be from late in the first century (after the synoptic gospels, but not long after) or late in the second century. Some think it contains sayings from Jesus that are independent of the synoptic tradition; others that the author largely copied from the synoptics.

If you glance at the lines that I have numbered 5 and 7 you will notice that the wording is very similar, even across all five columns in the case of line 7. In line 7 I have put two Lukan columns, one for where he has copied from Mark (column 3) and one where he copied from Q (column 4). We know that column 3 is from Mark because it comes in the same place in the narrative, just after Jesus has told the Parable of the Sower and its interpretation, and because Luke has copied both verses 21 and 22 and adapted verse 23 of Mark. The duplicate in column 4 must therefore come from Q (of course, I am simplifying here). However, his use of Mark has been influenced by Q, in that he has added a clause about who sees the light. I shall come back to explanations for some of these differences later.

So, next we ask, “Where did Mark and Q get their material from?” The first disciples and other followers of Jesus in Palestine would have rehearsed sayings and events they remembered. From these beginnings, the oral traditions about Jesus developed. The sayings were used by the early Christians in different circumstances, and the sayings were adapted and explicated. Some remained isolated, but others were gathered together, perhaps into short documents or into memorable sequences of sayings. These then formed the basic resources of Mark and Q and, indeed, for the supplementary material that Matthew and Luke also added to their gospels. Often these catenas of sayings were held together, not by a string of logical connections but by a series of catchwords that they shared. Sometimes the same word was the catchword across the string of sayings, sometimes a new catchword would be picked up from the end of one saying to make a fresh link to the next saying. There is a long series of sayings like this in Mark 9 that ends with the salt sayings (labelled 2 on the sheet). The series of three sayings in Mark 4 are a short example: it begins with light, then the catch-thought is hiddenness, and then about hearing secrets. In Luke 11 in line 7 the sequence of four sayings from verse 33 to 36 is linked by the word ‘light’.

We can gain an insight into the changes that may have happened to sayings from the time they were uttered by Jesus of Nazareth to the point they arrived in the written gospels by looking at the way the gospel writers handled the material. It is especially insightful to look at how Matthew and Luke handled the material in Mark and Q, and the further changes wrought by Thomas adds to this understanding.

Perhaps the most important thing to notice is that each saying is relatively detachable and can be moved from one setting to another. Matthew has taken the salt and light sayings from different sources and strung them together, while also omitting two out of the three salt sayings in Mark and three out of the four sayings that Luke has taken from Q. He also inserted into the string the saying about the city set on a hill (line 8). Thomas places that saying at verse 32, then begins verse 33 with a saying used by Matthew and Luke elsewhere (see 6), and finally returns in 33b to the lamp under the bushel. As a saying on its own is rather gnomic, it gains much of its meaning by its application and this is revealed by the context into which it is applied. This suggests that even if a saying goes back to Jesus, we can only guess how he used it and in what context, and so what he might have meant by it. We can, however, have a better stab at interpreting what the gospel writers meant by it through the context of where they have placed it.

Often we are assisted in this by additions they, or their predecessors, have made to a saying, most commonly by adding a prefix or suffix. A preface provides a context and a suffix offers an application. The saying about the candle and bushel is given an application in Mark: the original saying might seem to be about letting lights shine, but the application is a warning – anything you might hope to keep secret will have its bushel taken off and everyone will see it. It is then followed by a standard warning that is found frequently in the synoptics and Thomas. Luke, however, appends the standard warning, interpreting the saying much more threateningly. For the salt saying, Mark provides an application by tagging on the moralism to have peace with one another.

Matthew provides prefixes, saying that the hearers are salt and light to the world. These are a little like mini-chapter-headings. They introduce each topic and steer the interpretations of the sayings that follow. He also ends the sequence with his application – his followers should shine before men. This, then, introduces the ethical instructions that follow in the Sermon on the Mount. The evidence that these are Matthean is not just how they function in his discourse but also that these sentences are full of vocabulary that Matthew frequently uses but which is rare in Mark and Luke.

The wording of the saying can also be changed, but usually quite subtly. Matthew and Luke both improve Mark’s Greek style, for instance. Sometimes the change may be more pointed. Q had a suffix that implied the light saying was about enlightening people. Luke writes that these are people coming into the house (perhaps thinking of a Christian community), but Matthew is keen to stress that Christianity is for everyone and so the light is given to ALL. Thomas also sees that the light should be shared and writes that it is for those coming out, although this makes no sense of the imagery of a light within a house.

Sometimes, perhaps like Chinese whispers, a saying seems to have ended up with no meaning at all. The first of the Markan sayings on salt (see 2) is like this, “Salted with fire” is very mysterious. Matthew and Luke both deal with it by just omitting it. Interestingly, we can follow the later trajectory of this saying in the handwritten copies of Mark. As someone was writing out this sentence they decided it must mean something and that scripture would provide the meaning. So they added some words from Leviticus about salting a sacrifice before burning it with fire. Later copyists dropped the original saying entirely, just leaving the text from Leviticus.

I find all this detective work, tracing the antecedents of our gospel texts, fascinating. Yet, if one was being provocative, one might ask, “With all this mucking about of the Jesus tradition, does anything come from the man himself?” An attempt at an answer was provided in developing what are termed Criteria of Authenticity. The idea was that one could sift sayings with these criteria and come up with a set that probably went back to Jesus, ‘dominical sayings’. It was never claimed that this was anything more than probability and judgement. And there is always the temptation to discover a Jesus in one’s own likeness, who said just what one would want him to have said. Partly for these reasons, but also, I feel, because of the ideologically secularist assumptions of modern academia, the Criteria have fallen out of academic fashion. Not sharing that assumption, I consider that the Criteria have some value if used cautiously.

Now is not the moment to review all the Criteria, but some are closely related to what I have been describing. One is multiple attestation. If a saying is transmitted by both Mark and Q it must be at least early. Another criterion is a plausible reconstructed transmission history that shows how less original forms could be derived from more original ones – reconstructed using the patterns of change illustrated in my analysis of Matthew 5 and its parallels. Thirdly, the criteria of embarrassment and uniqueness might be applied in our case to the saying about salted with fire as it was retained despite it no longer making sense to people. That saying also has some historical plausibility and coherence. The historical Jesus was certainly executed and some notion of being ready for acute persecution would fit his context. However, providing a putative context for sayings has to be largely guesswork.

In recent decades, scholarly attention has shifted to the study of the texts as they have come down to us. This secular move happens to coincide with a conservative theological mood that takes the text of the New Testament as-is as the authoritative Word revealed by God. These moves allow biblical scholars to apply to a gospel a range of contemporary critical approaches such as narrative criticism, feminist criticism or post-colonial studies. In doing this, much attention is directed to the placement of sayings and narratives within a gospel’s structure, assuming that the gospel writers composed their books with care over these matters or, maybe, the placements reveal their subconscious presuppositions about meanings. At the very least, the sequence of sayings in their books does provide an actual context as an interpretive frame for the reader. Even so, the varied readings are no less disparate than the results of the old criteria of authenticity, and they are no less vulnerable of coming up with interpretations that suit the personalities and ideologies of those using these methods. However, I don’t think we have to end on such an uncertain note. If we take the candle under a bushel saying, for instance, Mark sets it just after the Parable of the Sower as part of his explanation of why Jesus was not recognised as the messiah in his own lifetime. Such a meaning is necessarily anachronistic on the lips of the historical Jesus. Matthew and Luke’s use of Q both focus on the importance of letting one’s light shine, which Jesus may have meant, but it is a truism. Yet all of them retain an element of threat or challenge around standing firm in one’s witness to truth. Salt that has lost its saltiness is cast out; nothing can be kept secret; be bold in proclaiming the light; and everyone shall be salted with fire. Whether this goes back to Jesus or not, and I strongly suspect it does; there is a commonality in the message: Stand firm in persecution. Whether I am right or not in my historical reconstruction, and what I am about to say may vitiate that, it does seem to me to be a crucial message for our own day. We are experiencing Western societies hurtling towards a lauding of selfishness, including a desire to repress critical voices. This is an understanding of the human condition which is the very antithesis of the Jesus tradition. Be ready then, for everyone shall be salted with fire.