A talk at Little Gidding on Eliot’s poem of the same name

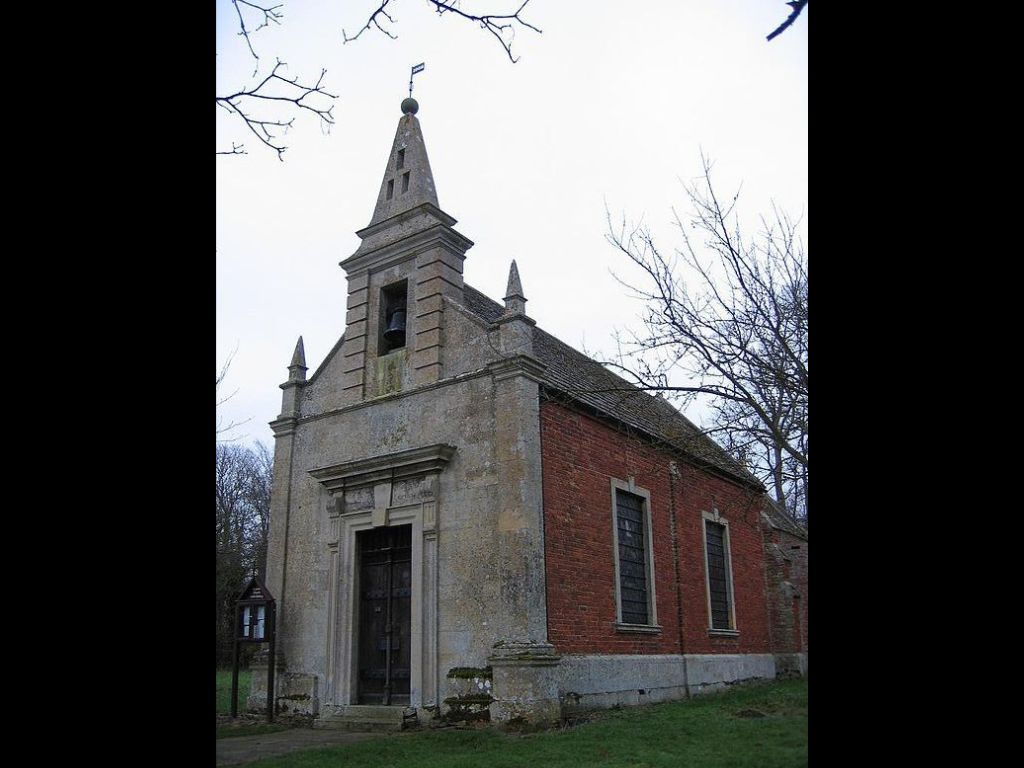

Following Nigel Walter’s sermon, many members of the choir visited Little Gidding church one evening. As the light was falling, Elsa gave an exposition of T S Eliot’s fourth Quartet, Little Gidding. This was for all, whatever one’s approach to religion.

She reflects on its setting in the time of war and related that to our present worsening situation. She pulls out of the poem signals of hope. And she sketches the vision of the poem of what a good community can be like.

Sermon by Elsa Stietman, Fellow of Murray Edwards:

Don’t you hate speakers who start with “I am not going to talk today about….”? And then go on at length about what they are not going to talk about? Alas, I will need to express some of my limitations in talking about Little Gidding: I cannot pretend to understand Eliot’s poetry (but love reading it). I am not a scholar of English and I cannot approach Little Gidding from the point of view of someone with a religious faith though, if I am considered a pagan, I would claim to at least being a Judeo-Christian pagan. I can hardly believe I have the audacity to try and convey something that might point to the core wrapped in the multilayered complexity of this text…

My experience of this poem is that it engenders fascination and enjoyment, of the wonderful elasticity of the language, its deceptive feel of it being the language of everyday [ “If you came this way, taking the route you would be likely to take…]; the elusive imagery which makes you read and reread, coming to the end and going back to the beginning:

“The end is where we start from. And every phrase

And sentence that is right (where every word is at home,

Taking its place to support the others,

The word neither diffident not ostentatious,

An easy commerce of the old and the new…” [V 221)

Eliot says it so much better than I can but I would like to dwell a moment on that last phrase “An easy commerce of the old and the new”. This poem, as all of Eliot’s poetry, is full of quotations, two kinds of quotations, the first kind rooted in Eliot’s profound knowledge and familiarity with classical and later European as well as English literature.

The second kind belongs to us, the readers, who will encounter many instances of what in German is called Aha Erlebnisse, that moment of recognition, of thinking ‘where have I heard or seen or read that before?’ Those of you familiar with biblical or wider religious reading will come across much that echoes in your memory (“All shall be well and all manner of things shall be well”?) as do phrases and situations reminiscent of, for instance, Dante, and Shakespeare.

An important element of the genesis of Little Gidding (published in 1942)is that of war and maybe Eliot’s own strong sense of mortality: he was not in good health and knew firsthand the horror of the Blitz, the period from September 1940 to May 1941 when the Germans bombed London as well as other parts of the country.

Many of the tensions, contradictions and contrasts in the poem are caused by the experience of living through war whilst somehow trying to keep alive a sense of perspective, of trust in humanity, of faith in ultimate salvation and of seeking respite in a place unaffected by war, steeped in spirituality, where inner peace might be found. Little Gidding is such a place but becomes more than that: it can be read as representative of almost any religious community, a place where people live in harmony with each other and with their environment, where there is a singleness of purpose, serving God, and a lasting mainstay for living life: the awareness of, and faith in, God.

For example:

“Midwinter spring is its own season

Sempiternal though sodden towards sundown,

Suspended in time, between pole and tropic”. [I, 214]

We are now, perhaps not quite in midwinter spring but in the time of year where we can sense spring coming even though “the dark time of the year” is still more than a memory. There is despair “Where is the summer, the unimaginable Zero summer?” and yet the hope that

“If you came this way in May time, you would find the hedges

White again, in May, with voluptuary sweetness.”

The journey through the poem, through life, is a journey to find peace, to make peace with one’s own mortality perhaps, and Little Gidding offers timeless respite and the permission to just be:

…………….“You are here not to verify,

Instruct yourself, or inform curiosity,

Or carry report. You are here to kneel

Where prayer has been valid.”

Throughout the poem the contrast between the living and the dead is evoked often, a frightening contrast but also one that gives perspective: we are aware that:

“Here, the intersection of the timeless moment

Is England and nowhere. Never and always.”

We are part of the chain of being which connects the past to the present and by being aware of the past and learning from it, we might hope to shape the future better:

…………………….“A people without history

Is not redeemed from time, for history is a pattern

Of timeless moments. So, while the light fails

On a winter’s afternoon, in a secluded chapel,

History is now and England.”

We are, in our own present, aware of war and destruction, perhaps more than ever since the end of the Second World War, after which such high hopes came into being, of a world striving for harmony, of United Nations, of solidarity, of NATO, of, gradually, the growing awareness that we needed to be the caring stewards of our earth and all its resources. So much of that is dismantled now and the despair Eliot voices is one that we might feel in our own time.

But , Little Gidding also offers hope: we are capable of learning from past mistakes, of coming to understanding and insight, of rekindling hope, and of loving and living and trying to achieve unity and harmony:

“We shall not cease from exploration

And the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time.”

We might be aware of the enormous effort continuously needed in achieving inner or external peace:

“A condition of complete simplicity

(Costing not less than everything) but

“All shall be well and

All manner of thing shall be well…”

Leave a Reply